Artist-Surfer Simon Benjamin Explores How Black People Relate to the Sea

Artist-Surfer Simon Benjamin Explores How Black People Relate to the Sea

Of all the songs that played during my hours-long visit to Simon Benjamin’s Brooklyn studio, “The West” by Althea and Donna echoed in my head the most—partly because it’s catchy, and partly because its refrain (“the West is gonna perish”) complements Benjamin’s current question: “how productive is nationalism right now?”

Benjamin is a multidisciplinary artist driven by curiosity. Previously an avid surfer, he’d travel to coastal regions from Hawaii to Senegal to surf on tranquil waves. These experiences made him question why he was often the only Black person in the water. Soon, Benjamin devised a series of questions about the “complex relationship African diasporic people have with the sea.” Centred around his native Jamaica, his artworks take shape in the aftermath of the transatlantic slave trade and examine the brutal relationships Black people have with the ocean, global trade, and migration.

The St. Andrew–born geopolitics-minor-turned-artist has always been concerned with matters of international relations and national identity. Growing up in a family of national service sector employees—Benjamin’s mother was a stewardess for Air Jamaica, and his father was in the Jamaica Defense Force—there was a “great sense of national pride” within his household, given that his parents were among the first generation to witness the island’s transition from colony to independent nation. Benjamin credits family discussions around Jamaica’s political history and MTV music videos as things that broadened his understanding of culture.

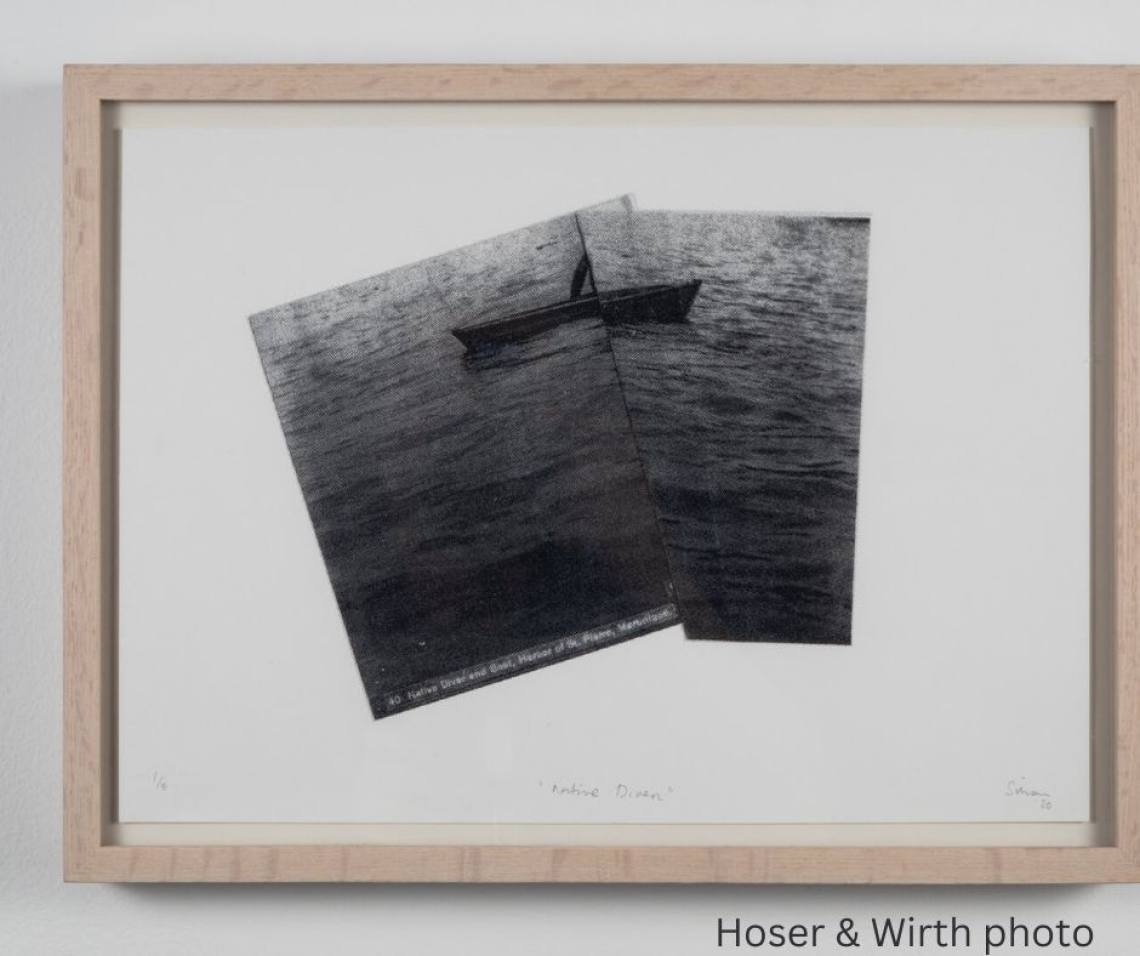

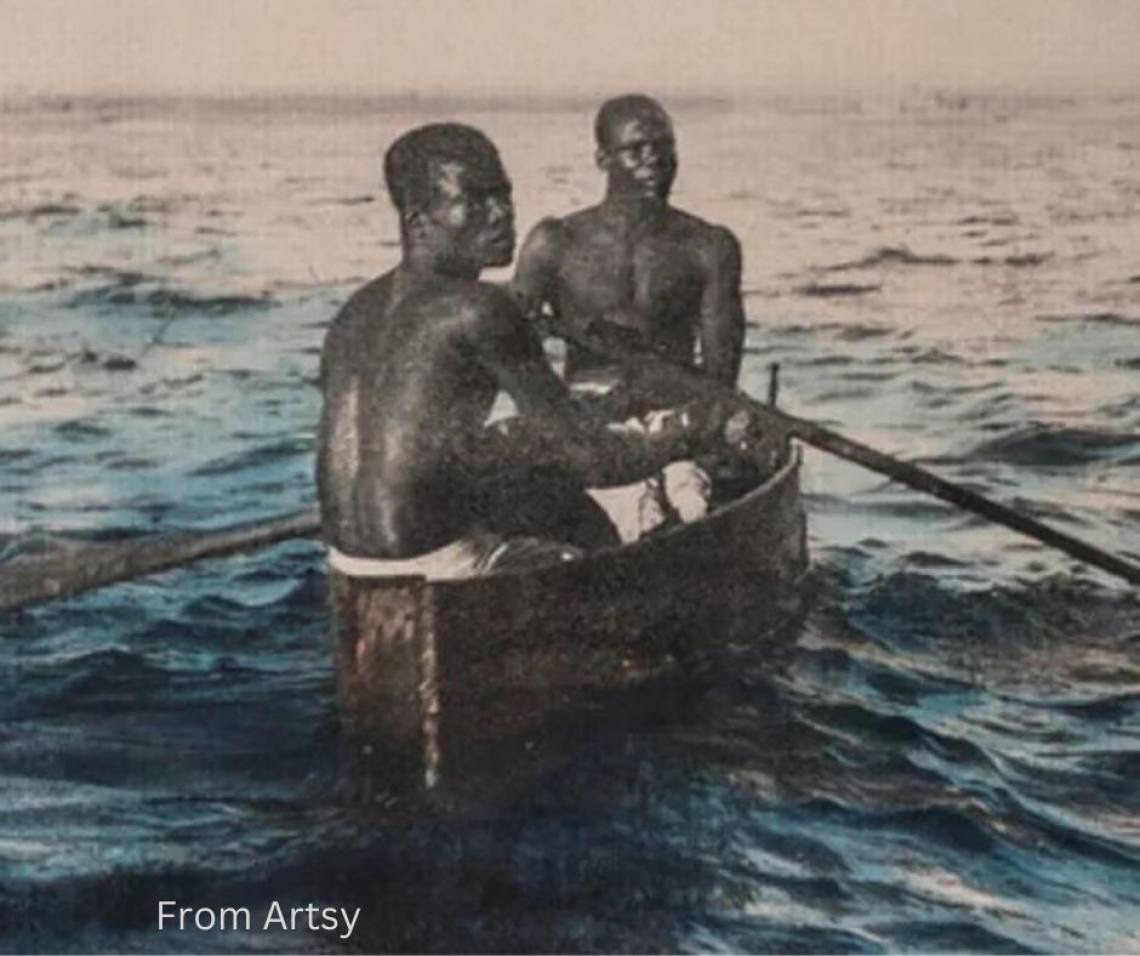

Through his artworks spanning photography, film, installation, painting, and sculpture, Benjamin speaks to ecological devastation and political friction, honouring all that has fallen prey to the horrors of modernization. For Barrel 1—South Coast, Jamaica (2024), Benjamin compiled cornmeal, sand, beach debris, and resin into a cylindrical form that considers deep time and the impact of colonialism on the landscape, as well as citizens’ waning access to fresh fish and the island’s coastlines.Archival 19th-century photography is central to Benjamin’s practice. Such images were tools of propaganda that romanticized the Caribbean as a utopia after decades of associating the region with savagery and malady. In his recent New York solo show, “Native Diver,” at Swivel Gallery, Benjamin forgoes the sensationalism of a Caribbean fantasy by embracing neutral hues and minimal forms, eschewing lush pigments and dramatic compositions. Native Diver (2024), a black-and-white silkscreen painting, has a fold at the centre that conceals the figure in the boat. Like Barrel 1, it expands the hallmarks of Caribbean aesthetics and encourages the multiplicity Édouard Glissant encourages in his 1990 book Poetics of Relation.

Altogether, Benjamin’s artworks affirm a global interconnectedness that prevails beyond borders. In this year’s Malta Biennale, he presented an interactive video installation, Pillars (2024), made with shipping barrels often used by immigrants to send goods back home. Bored into the barrels are apertures that act like portals: through them appear diorama-like video seascapes that migrants encounter in their journey toward safety. Like much of Benjamin’s work, the piece highlights the ways our histories are bound by a single body of water. Now, all we must do is blur the lines that divide.

September 2024

Copyright © Experience Jamaique. All Rights Reserved. Designed and Developed by LucraLux Marketing.